Lucibello's Pastry Shop

935 Grand Avenue, New Haven, CT, 06511

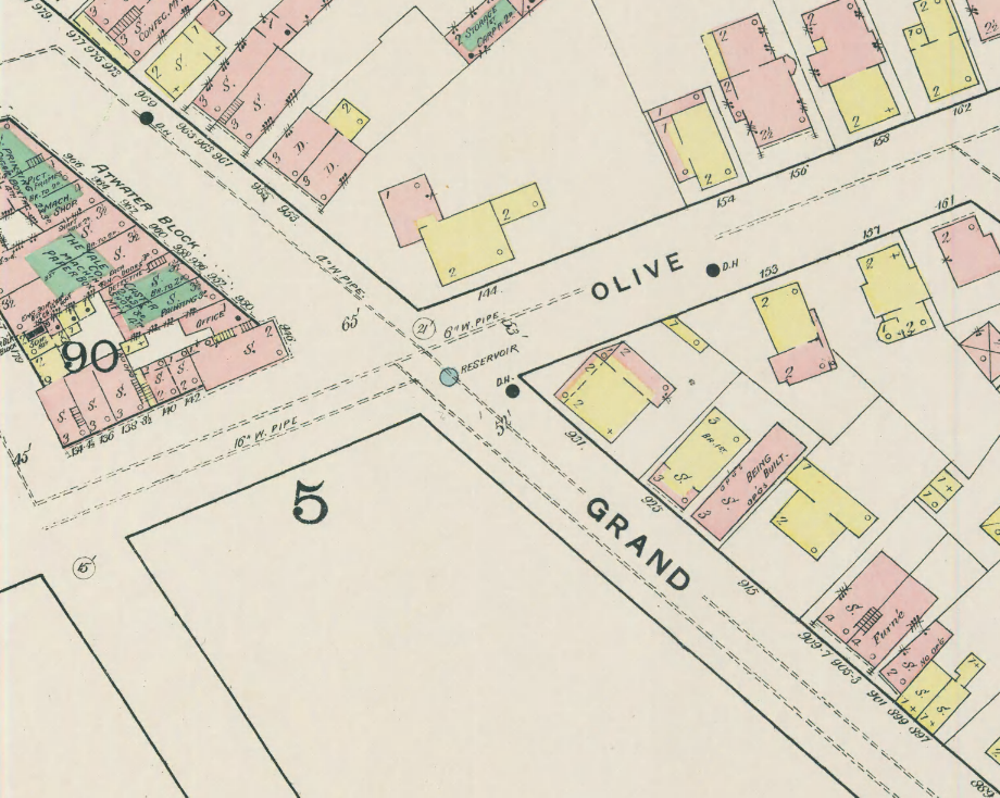

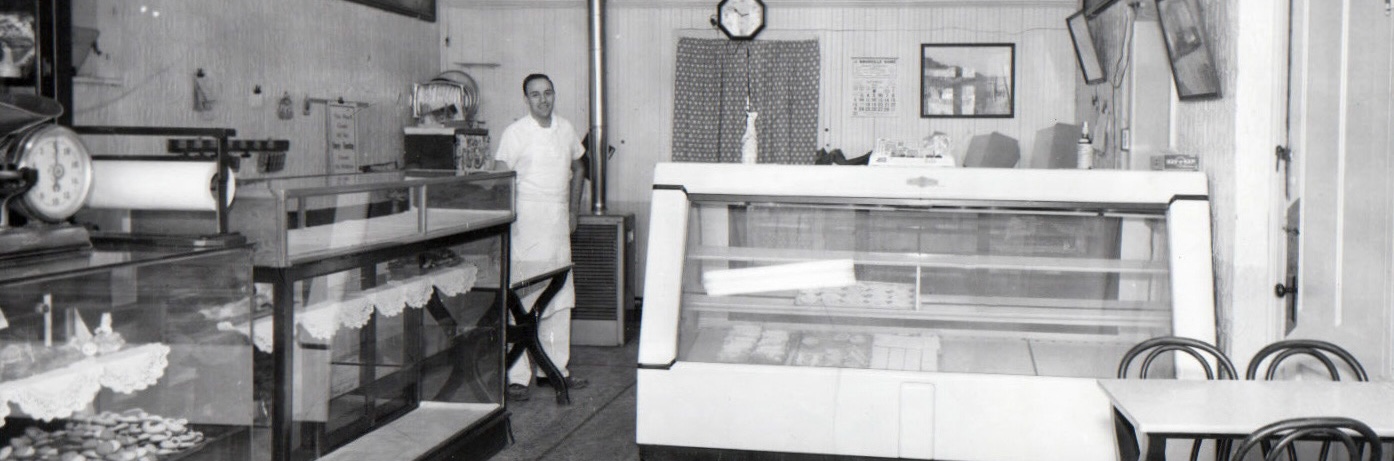

Growing up in Italian-American family in the New Haven area, I was raised on pastries from Lucibello’s. My grandpa was partial to Lucibello’s flaky, ricotta-filled sfogliatelle that shattered as he bit into them. My mom loved the pasticiotti, little muffin-looking confections that exploded with vanilla cream and a puff of powdered sugar. They used to joke that going to Lucibello’s was like stepping into a time capsule. “No one makes pastries anymore like they do,” my grandpa always said. He refused to go anywhere else. It turns out my mom and grandpa were more right about Lucibello’s time-capsule qualities than they could have imagined. Almost nothing has changed about the building or business since the Faggio family moved in 1962 to the wedge of land where Grand Avenue slices through Olive Street. In fact, the only change between the blueprints in the New Haven Building Department and the present-day building is the absence of built-in flower pots on the Grand Avenue side. (A new roof was installed in 2000 at a cost of $7500.) In 1962, Lucibello’s new building (built at a cost of $22,500) was less of a time capsule than a glimpse into the future. As lot B-11 of the Mayor Dick Lee’s Wooster Square Redevelopment Project, the building represented a new vision for New Haven. The project was critical for Mayor Lee. In building the highway, he hoped to clear one of the cities poorest and most deteriorated area as well as ingratiate himself with the hard-to-crack Italian Republican stronghold of Wooster Square. To that end, his administration worked incredibly closely with the Wooster Square Renewal Committee to ensure the Italian community’s needs were met at all steps of the project. Lucibello’s is a testament to that attention to detail. From its founding in 1929, the bakery had been located on the ground floor of a traditional four-story building on Chapel Street—directly in the path of the new Interstate. Though most of the surrounding neighborhood was considered blighted and later destroyed, the Lee administration recognized Lucibello’s as a pillar of the neighborhood’s Italian community and gave it arguably the best location on Grand Avenue, the strip designated for commercial activity in the Redevelopment Project. It stands there now, as it did even more so then, as a gateway to the neighborhood— a declaration and demarcation of the neighborhood’s ethnic history. Just as Lucibello’s new building served as a link to the Italian community, so too did it represent a link to the new New Haven as a whole. The building’s clean modernist lines—designed by Damuck and Painchaud, a New Haven firm led at the time by Yale grad Kelton Painchaud—place it in conversation with the iconic Fire Department headquarters building that looms large across the street. The aesthetic connection between the two buildings—between Lucibello’s oven chimney and the Fire Department’s hose tower, in particular—suggests Mayor Lee’s desire for a close bond between his administration and the community he hoped to win over. (It’s also possible that the Lucibello’s building functioned as a Trojan Horse for the Mayor’s development plans. That is, if the neighborhood’s favorite bakery looked new and modern, the neighborhood’s residents might be more comfortable supporting the mayor’s future modernization schemes.) Examining the immediate area surrounding Lucibello’s site helps further contextualize the changes that Lucibello’s represented when it moved to the site. On the 1886 Sanborn Fire map, a brick-and-wood dwelling stood on the site surrounded by a few small businesses on Grand Avenue and well-spaced dwellings on Lyon Street one street away. By 1924, Grand Avenue appears to have developed into a tightly packed commercial strip. Though the same dwelling stood at the Lucibello’s site, the rest of the street was now filled with small stores, each one pressed up against the next. In 1954TK, the dwelling had been replaced with a stone gas station, suggesting the rise of automobility in the city. The rest of Grand Avenue remained heavily commercial, though some of the small storefronts had been combined into larger stores. Fast forward to the 1973 Sanborn Maps, and the neighborhood had changed drastically in the post-Redevelopment era. Surrounding Lucibello’s were a few big stores and many large parking lots, designed of course, to lure in suburban shoppers back into the city. We now know the legacy of that decision. While Wooster Square fared better than many other neighborhoods thanks to its Renewal Committee made up of locals, it’s hardly the bustling commercial district it once was. And while there are relics of the area’s Italian past—Lucibello’s itself, as well as Pepe’s, Sally’s and Libby’s on Wooster Street—today they are more reminders of a past than representations of the neighborhood’s current reality. Perhaps most tellingly, Peter Faggio, Lucibello’s third generation owner laughed when I asked him if his family still lived in the neighborhood. “No, no,” he told me. “I live in Durham with my family. We moved out a long time ago.” To get to work, he takes I-91.

https://lucibellospastry.com/about-us/

https://walknewhaven.org/lucibellos-pastry-shop

Researcher

Ryan Healey, Karina Encarnación

Date Researched

2025

Entry Created

June 4, 2017 at 8:47 AM EST

Last Updated

June 24, 2025 at 6:23 PM EST by karinaencarnacion

Style

ModernistCurrent Use

CommercialCommercial BakeryCoffee/Tea/Ice Cream/YogurtCaféEra

1950-1980Neighborhood

Wooster SquareTours

Grand Avenue: Gateway to Fair HavenYear Built

July 27, 1962

Architect

Damuck and Painchaud

Current Tenant

Lucibello's Pastry Shop

Roof Types

FlatStructural Conditions

Good

Street Visibilities

All sides of the building can be seen from the street as it sits on the corner of the lot, backed by a large parking lot

Threats

DevelopmentVandalismExternal Conditions

Good; building itself is in good condition while the concrete paving and sidewalk surrounding it could be improved

Dimensions

Approx. 68 x 32 x 11'

Street Visibilities

All sides of the building can be seen from the street as it sits on the corner of the lot, backed by a large parking lot

Owner

Faggio family

Ownernishp Type

Private

Client

Lucibello's Pastry Shop

Historic Uses

CommercialCommercial Bakery

Comments

You are not logged in! Please log in to comment.