Chamberlain Building

50 Orange Street, New Haven, CT 06510

While the Chamberlain Building currently houses the gallery spaces of Artspace New Haven and a group of apartments belonging to the Residences at Ninth Square, it spent most of its lifetime as a center for the manufacture and sale of furniture. Its namesake, the Chamberlain Company, moved in immediately following the building’s construction around 1880 and remained for more than eighty years, a fixture of a bustling commercial neighborhood. The building’s simple rectilinear form and spare ornamentation speak to this functional past. The middle of the twentieth century brought economic hardship to the Ninth Square neighborhood, which was reflected by more rapid turnover of the Chamberlain’s tenants and which ultimately gave rise to the redevelopment projects that spawned the creation of the Residences at Ninth Square. Now, the building serves as a durable example of late-nineteenth-century commercial architecture while reinventing itself as a forward-looking hub for the activation of a progressive New Haven arts community.

- c.1880 - 1962: Chamberlain and Co. (aka the Chamberlain Company, Chamberlain’s)

- 1963 - c.1970: Yale Furniture Co.

- c.1980 - c.1990: ACME Office Furniture Incorporated

- 1993 - present: The Residences at Ninth Square

- 2002 - present: Artspace New Haven

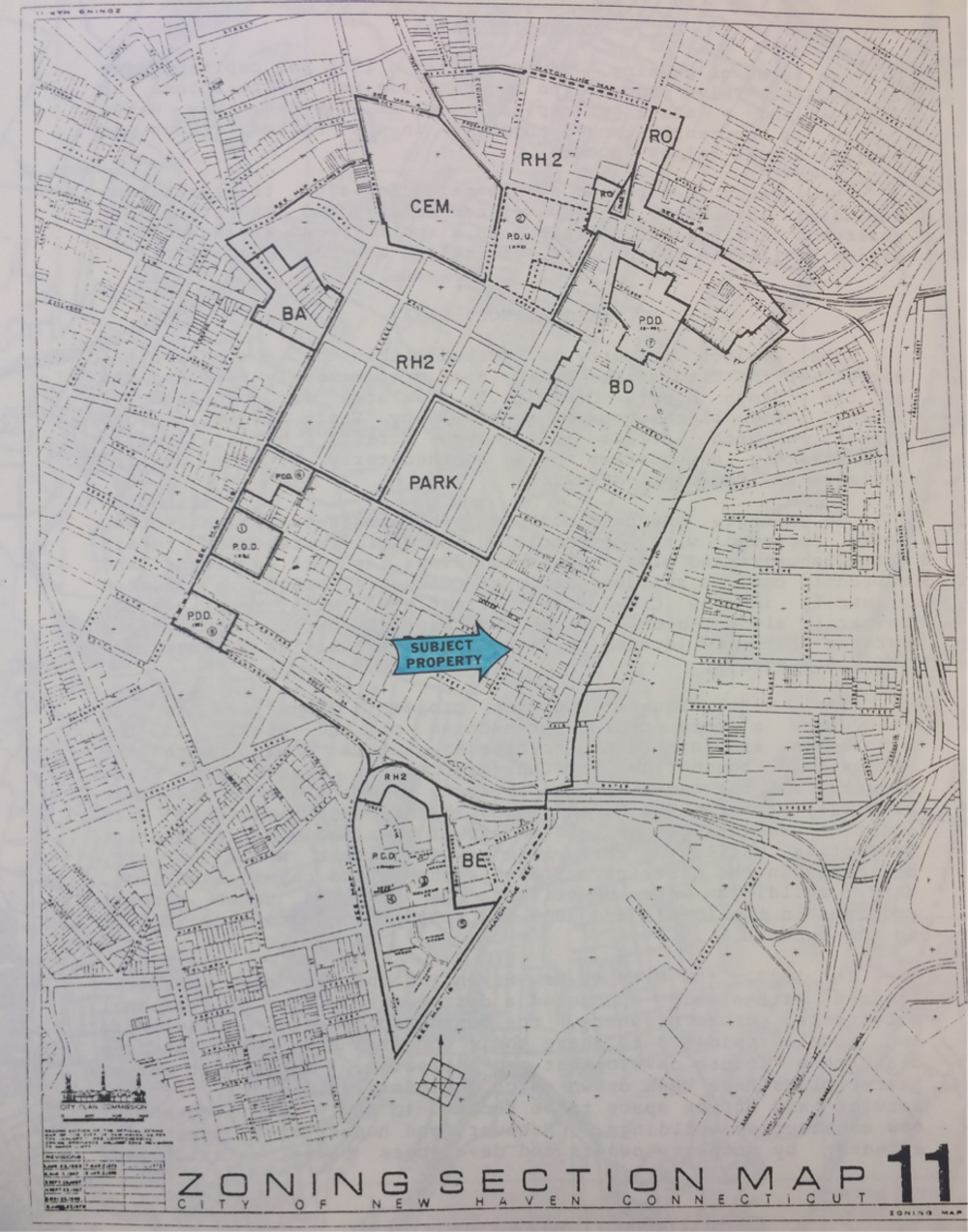

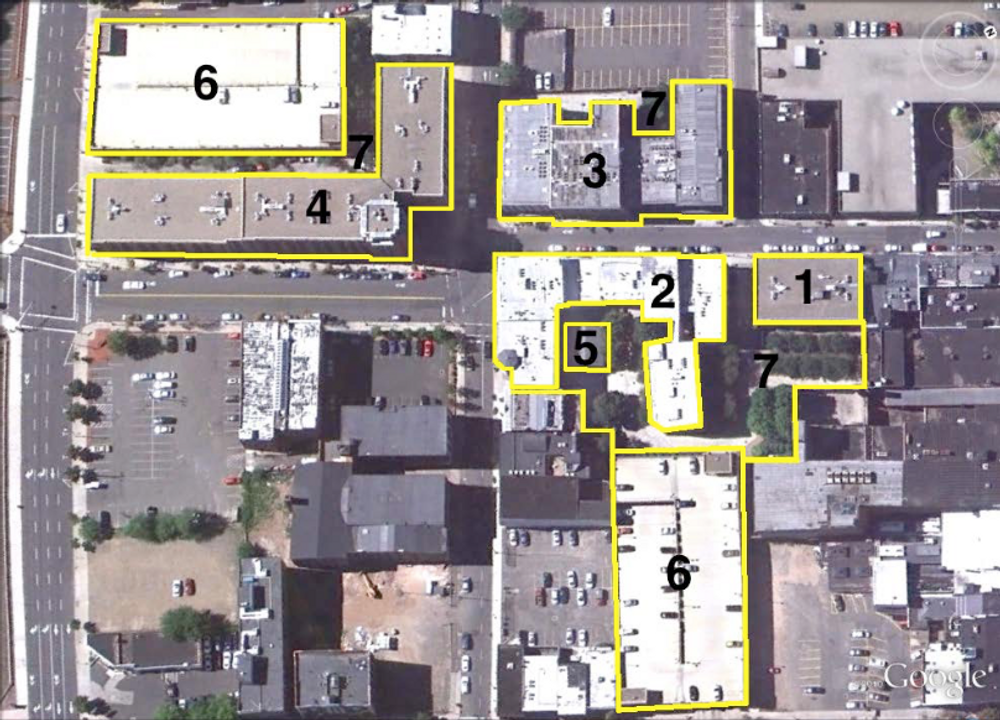

The Ninth Square forms part of the historic core of New Haven, laid out in the original 1638 nine-square plan at the time of the city’s founding (3) following inhabitation by the Quinnipiac Indians prior to European colonization. Originally, like the seven other non-central squares (the central square comprised the city’s civic center and the New Haven Green), the ninth square accommodated the dwellings and associated barns, gardens, and small businesses that supported New Haven’s early agricultural economy (3).

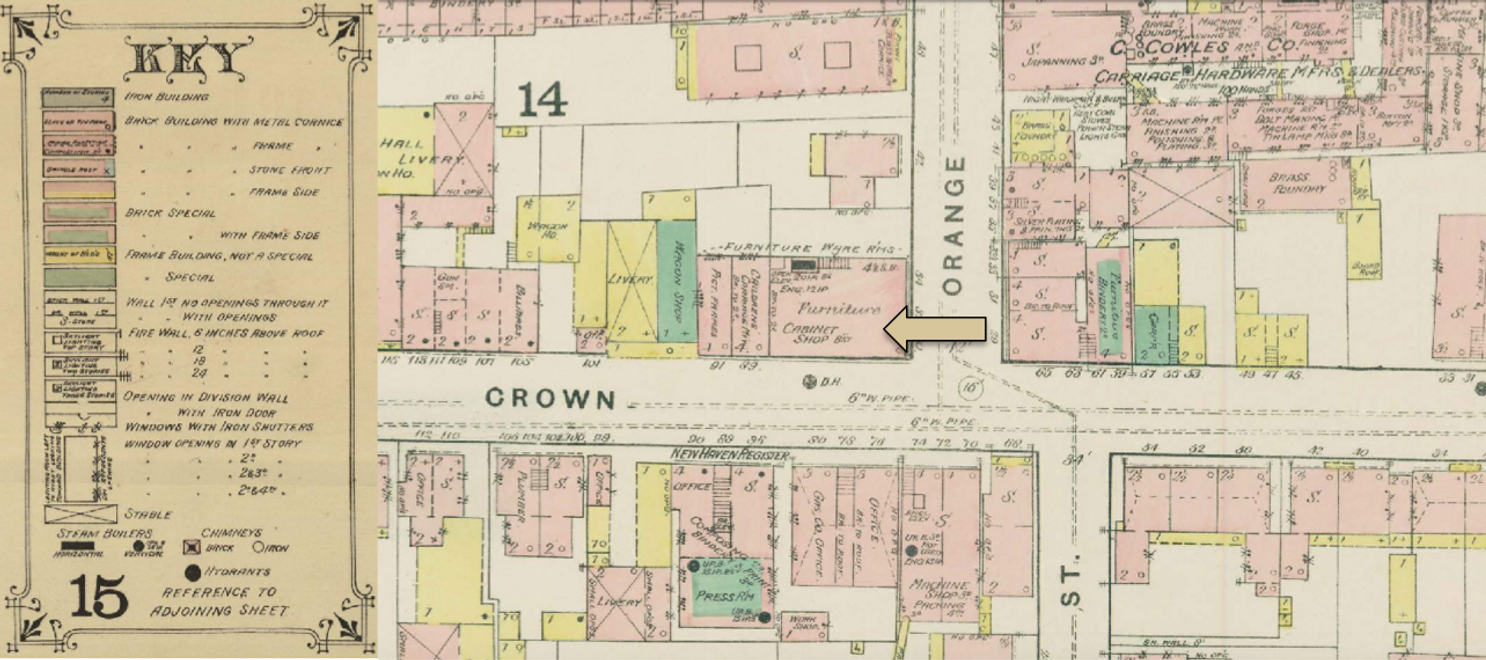

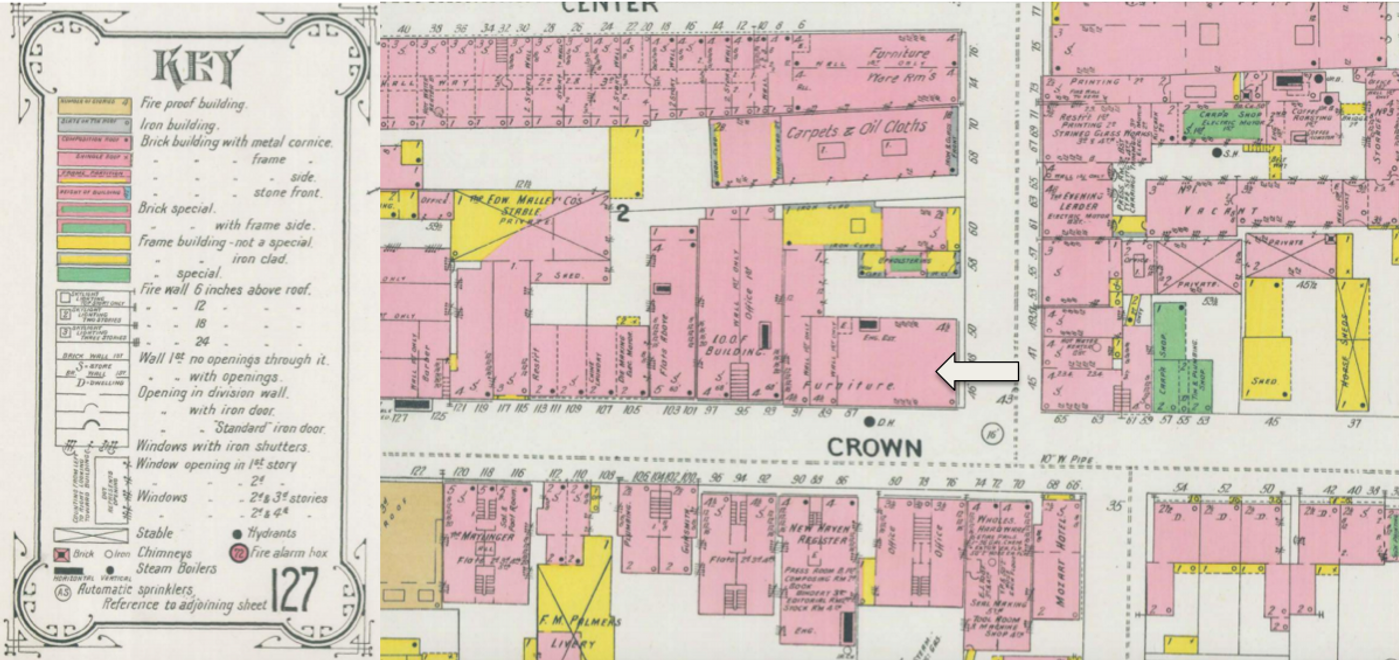

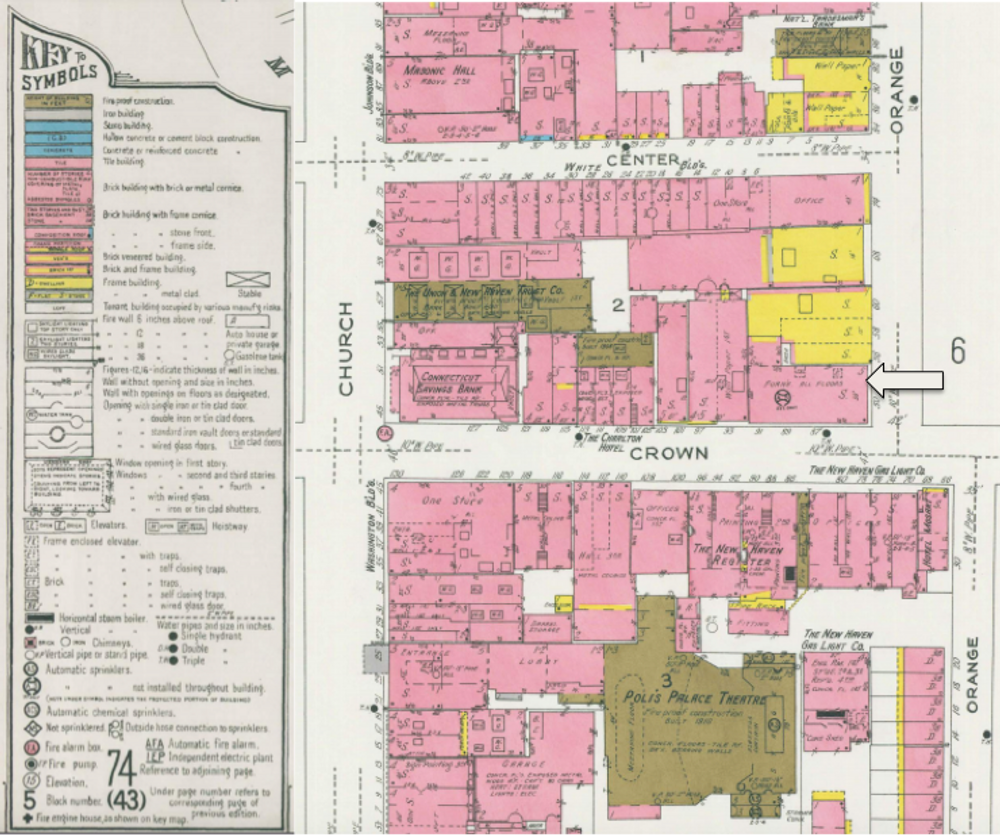

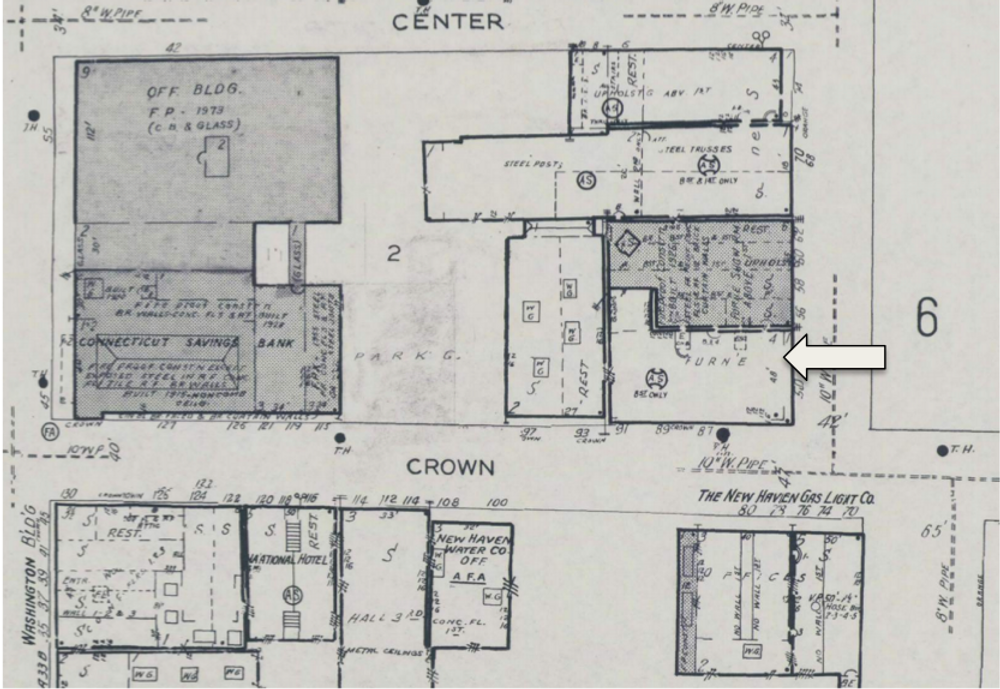

Of the nine squares, however, the ninth is closest to the harbor and to Long Wharf and therefore experienced the greatest concentration of mercantile business. By the 1920s, the construction of the Farmington Canal, which offered an inland route north from Long Wharf to the Connecticut River in Northampton, Massachusetts, strengthened the commercial character of the neighborhood (3). At this point, the area began to lose its residential character as vacant land was filled with new construction and residential structures were converted for commercial use (6-9). Through the second half of the nineteenth century, the Ninth Square became central to the city’s participation in the industrialization of Connecticut. It was home to a growing number of light manufacturers (6-9). By the time of the construction of the Chamberlain building in the late nineteenth, its now characteristic rows of continuous commercial blocks were established; it was in this context of commercial and industrial development that the current structure at 50 Orange Street was erected.

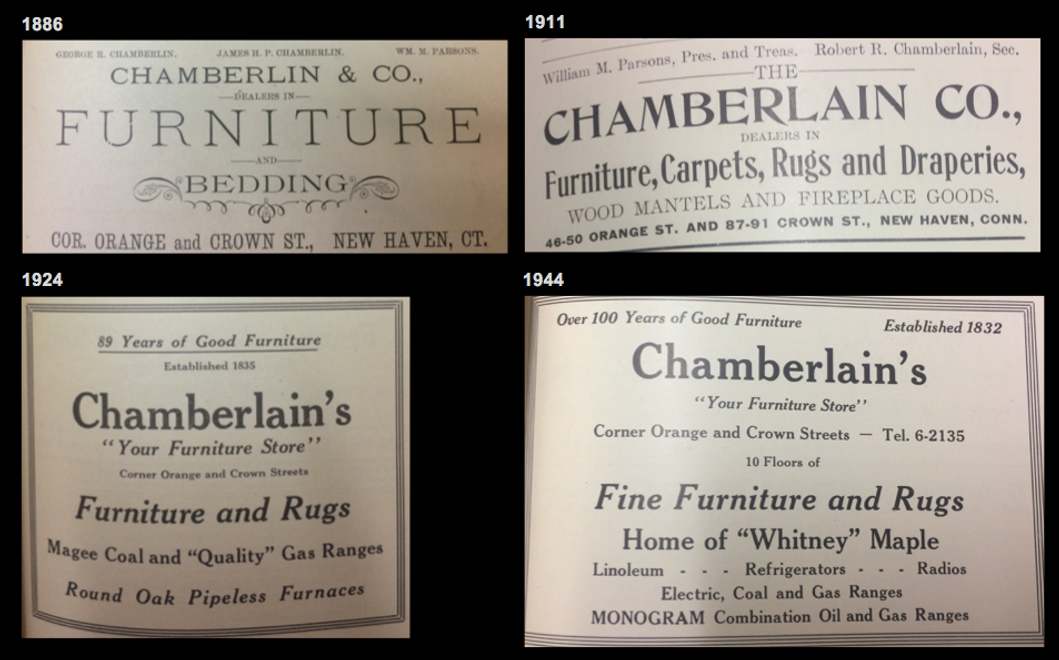

The first business to fill the Chamberlain building following its construction around 1881 was its namesake, furniture and bedding dealer Abel C. Chamberlain and Company (5). Prior to the business’s founding as the first furniture retailer in the Ninth Square in 1832, the Chamberlain family carried a tradition of furniture-making traceable to 1636, when Edmund Chamberlain, a cabinetmaker, emigrated from England (4). In 1882, the Chamberlains moved their operation from 388-392 State Street to what is now known as the Chamberlain building, situated in what was a rich commercial neighborhood at the time (1). In the years following their establishment on the corner of Orange Crown, the Chamberlains were surrounded by a variety of mercantile and manufacturing businesses, such as builders, contractors, architects, publishers, realtors, and sellers of specialized goods (6-9). Following Abel’s death, his son George, and later their sons Robert and Robert Jr., continued the business in what is now known as the first retail furniture family business in the United States (4). From the Chamberlain building, they operated the administrative, manufacturing, and retail branches of the business. In 1926, architect Jacob Weinstein was commissioned to design an annex, which more than doubled the size of the store, and less than ten years later, the storefronts were added and the cornice removed (1). However, by the middle of the twentieth century, business suffered as the nation’s retail sector shifted its focus from individual proprietors of single goods to larger venues offering a more complete range of goods and national chains began to established low-priced department stores in New Haven (3). By 1962, Chamberlain’s relocated from the Chamberlain building, its home for eighty years, to Boston Post Road in Orange, Connecticut (1).

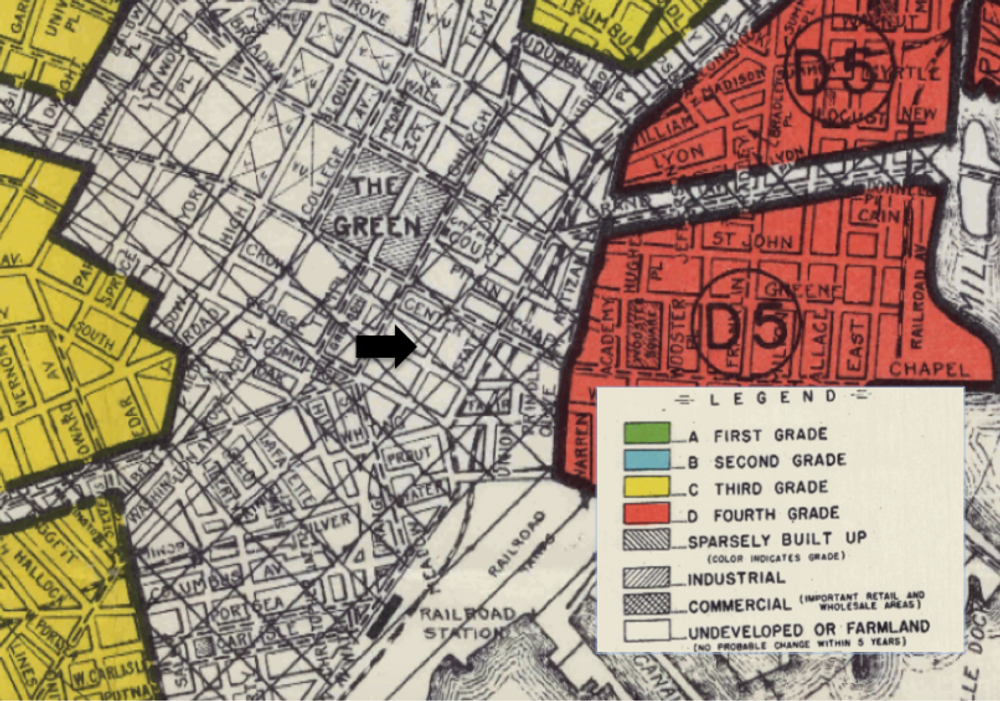

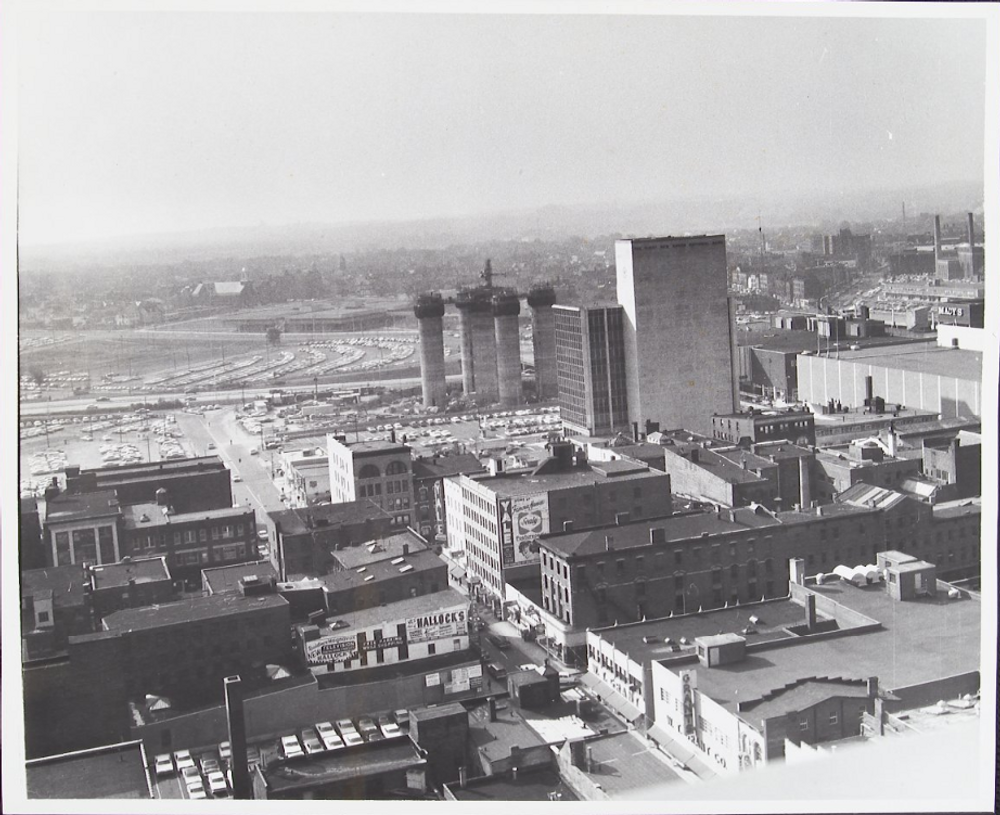

In the 1960s, Yale Furniture Co. (incorporated in 1949 by Saul Z. Lappen but no longer in existence) replaced Chamberlain and Co. at 50 Orange Street (10). At the time, buildings in the immediate surroundings suffered economic and physical decline as residents and commerce flowed to the suburbs, and many went vacant or were demolished for proposed urban renewal programs (2). After only a few years of occupancy by the Yale Furniture Co., the Chamberlain building, too, went vacant (5). However, its history as a retail center for furniture continued in the 1980s when ACME Office Furniture Incorporated (originally the American Moving Company, then ACME Moving & Storage Co.) moved in. From its space in the Chamberlain building, ACME supplied furniture to corporate workspaces, with clients including Southern New England Telephone, the New Haven Register, Yale, and City Hall (11).

Through the 1980s, the Ninth Square continued to struggle (3). Little remained of its previously vibrant commercial community (12), and it began to acquire a reputation as “derelict” (13) and “blighted” (14). Its late nineteenth-century commercial architecture deteriorated without appropriate maintenance—many of these buildings’ upper floors had been vacant for almost 50 years (12). At the same time, interest in the district accumulated among non-residents who were drawn to what they saw as the city’s last cluster of nineteenth-century commercial architecture to remain standing (2). In fact, the name “Ninth Square” arose in this period to bring attention to the neighborhood’s status as the last of the city’s original nine squares to receive redevelopment attention (12). The Ninth Square District Project arose with the objective of rejuvenating a “once prosperous section of the city” (2), and the district’s property owners and merchants aligned with development entrepreneurs to form the Ninth Square Association, funding research into the buildings’ original appearance and using it to support a successful bid for a place on the National Register of Historic Places (3). With the New Haven Preservation Trust and the Downtown Council of New Haven, they formed the Ninth Square Limited Partnership and made plans to “restore” the neighborhood by attracting investors and planning apartments with ground floor retail space (12). As this redevelopment project gathered steam, ACME lost the Chamberlain building lease, providing a blow to business (15); twenty-four other local businesses, including some founders of the Ninth Square Association, were displaced in the redevelopment process (12).

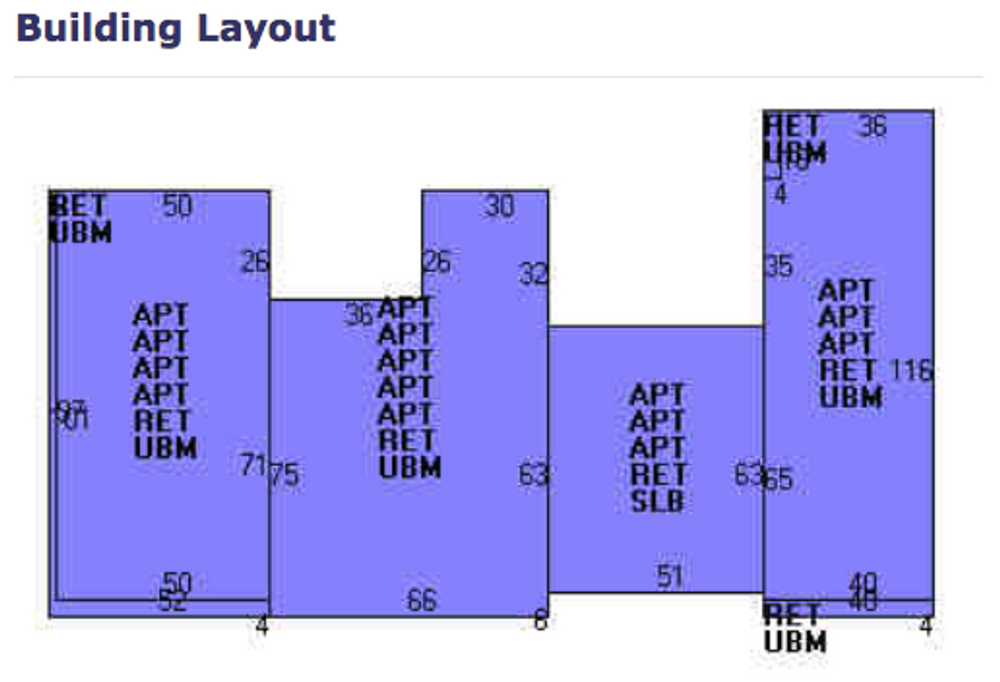

When the project temporarily stalled due to economic conditions and the unwillingness of lenders to provide a financing package, the Saint Louis housing developer McCormack, Baron & Associates, Inc. stepped in to re-envision the project in partnership with New York’s The Related Companies. Together, they built a mixed-income mixed-use development branded as “The Residences at Ninth Square,” which opened in 1995. The project, which cost just under $87 million, was funded with McCormack Baron’s “creative financing” methodology, which included investments by the Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, the city of New Haven, the Department of Housing, an Urban Development Action Grant, and equity generated through the sale of federal low-income housing tax credits and historic investment tax credits, as well as significant investments from Yale University, whose administration was eager to create a more prosperous “buffer zone” between campus and what was perceived as a crime-riddled downtown (12).

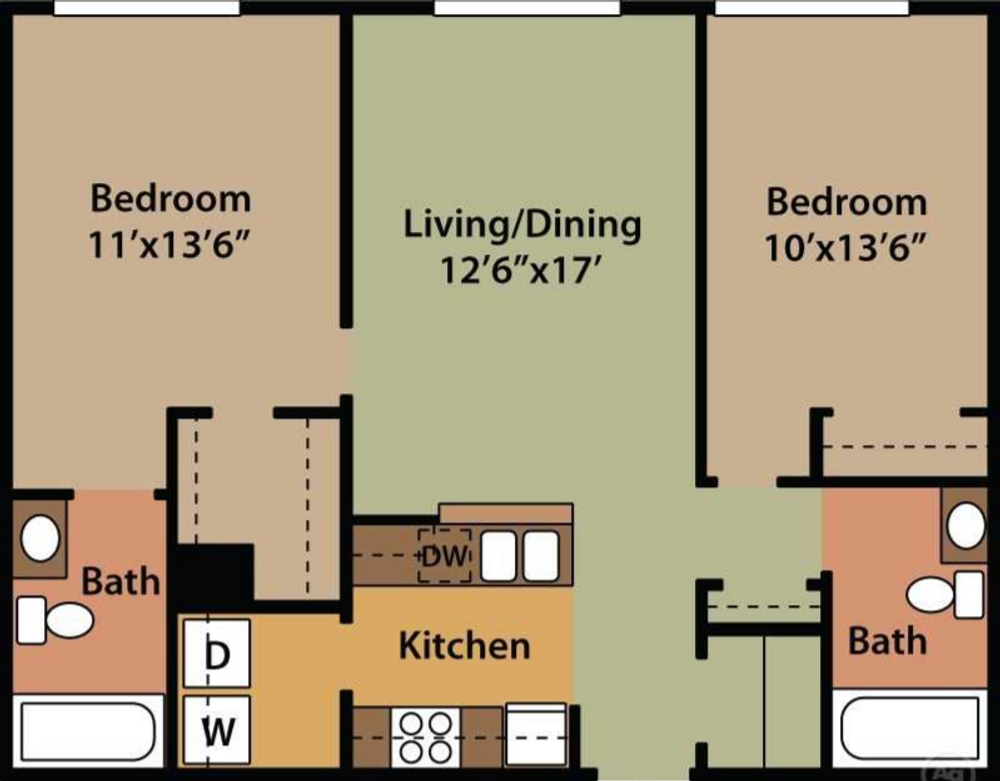

Collectively, the Residences at Ninth Square contain 335 studio, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom apartments on their upper floors and 50,000 square feet of retail on ground level, split between several buildings; the Chamberlain building houses the only two-bedroom, two-bath units in the development (12). Of the 335 apartments, 142 are reserved for tenants paying market-rate rents, while the remaining 193 (about 57% of the development) are set aside for tenants who qualify for a lower rental rate. To qualify, a tenant must make no more than 60% of the New Haven area’s median income as determined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, but McCormack Baron also requires that the must also be employed and make at least forty percent of the median income for the area (12). While some credit the Residences with “setting downtown on a positive growth trajectory” (16), others look critically towards the project for its lack of communal space, its strict qualifications for affordable unit eligibility, and its role as an agent of gentrification, displacing local businesses with ones that do not directly benefit the inhabitants of the area (12).

While the upper floors of the Chamberlain building still house the Residences at Ninth Square, the current tenant in the ground floor of 50 Orange Street is Artspace New Haven. Founded in 1986, Artspace is a gallery and nonprofit organization dedicated to championing artists from the New Haven area and building new audiences for contemporary art (17). Over its lifetime, the organization has served more than 6,000 artists (18). Through exhibitions, residencies, and educational and participatory programming, it seeks to activate conversations about social issues in New Haven social issues and promote investment by the New Haven community in its urban setting through “creative placemaking,” leveraging the arts to serve local interests. Since 1998, Artspace has run an annual City-Wide Open Studios festival through which 2 million square feet of underutilized or vacant space throughout the city have been activated and showcased for the benefit of artists and their supporters (19). The festival’s symbolic hub and central exhibition space is Artspace’s gallery space in the Chamberlain building.

To renovate the building and move into the space, Artspace entered into collaborative arrangement with the City of New Haven in 2001 (20). The Connecticut Department of Economic Development, the New Haven Development Commission, and the City Planning Commission supported the project. Architect Michael Haverland oversaw the restoration of the historic structure and the creation of new facilities, including a flexible exhibition space, window installations, offices, and a workshop for an artist in residence (20). The gallery opened to the public in April 2002 and today continues to offer Artspace a permanent physical home (4).

The story of the Chamberlain building and its broader surroundings traces the ways that power stems from and is exerted over the land—a strategic commercial location close to Long Wharf imbued the site with a certain cachet in the city’s early days of industrialization; its later years were marked by the exercising of institutional power to engage in renewal projects that were, at times, devastating to local communities. Now, from the Chamberlain building, Artspace is engaged with uncovering and conversing about these local histories. Walk up to the entrance, and one finds the site’s latitude and longitude coordinates prominently displayed, with “or 50 Orange Street” written below. Beside this unusual building marker is an inscription by the artist William Stone, printed onto the glass. It says, “When I first came to Artspace I noticed that there was no street number anywhere on the building. Here, outside above the entry door, I have remedied the situation, with a different locating system that is less temporal, more international, and with less cultural connotations. Who or what is the orange? And just how far is this formerly British colonial town from the center of the empire? It is a little more than 72 degrees west of the prime meridian at the center of the former Greenwich, England.” It’s a striking statement on the site’s role today in critically and radically reimagining space and power in New Haven.

The Chamberlain building sits squarely within the Ninth Square Historic District in the center of New Haven’s downtown business region (2). It contributes to the neighborhood’s rich fabric of modular, rhythmic commercial facades, mostly three to five stories tall, that almost continuously line the narrow street with little setback. The facades form corridors of commercial activity that speak to the centuries-old pattern of mercantile development in New Haven. While brick constitutes the dominant building material, the neighborhood’s architectural mosaic is rounded out by buildings constructed with brownstone, pressed metal, and cast-stone in styles that range widely, including Italianate, Georgian Revival, Greek Revival, Romanesque Revival, Queen Anne, Beaux-Arts, Neo-Gothic, and Art Deco (3). Anchoring the corner of Orange and Crown streets, the Chamberlain building is modestly ornamented and minimally stylized compared to the richly detailed and well-preserved nineteenth and early-twentieth century buildings that surround it, but it does offer an example of how architectural motifs from its more elaborate contemporaries tended to trickle into workaday utilitarian structures.

Today, this historic district continues to serve as a busy commercial thoroughfare, filled with automobile and pedestrian traffic. To the south rises the block-like brick tower of the Stonehill House, and just a block further the Knights of Columbus tower. Orange Street serves as an important New Haven thoroughfare, and just around the corner from the Chamberlain Building on busy Chapel Street, crowds frequently assemble at a nearby bus stop. Evidence of recent attempts to “revitalize” the neighborhood are visible—a “creative placemaking” public art project graces a chain link fence on Chapel Street nearby, decorative sidewalk stones are inscribed with information on the history of the area, and young tree plantings accent the streetscape. Immediately surrounding the Chamberlain building are upscale retail businesses—the Ninth Square Market, Barcade, Skappo Merkato, Euphoria Salon—that cater to economically advantaged customers. Across the street, the “Fresh Yoga” studio has recently gone out of business, yet another new vacancy in a pattern that has left local merchants concerned (4).

Planted on the corner of Orange and Crown, the Chamberlain building is physically imposing but not necessarily immediately dazzling. Its four and a half stories rise solidly and somewhat plainly from the street in a uniform block; its brick surfaces are painted pale beige. Ornamentation is minimal, its surfaces spare and utilitarian. Function, not fashion, seems to drive its commercial architecture. Sash windows, bordered by cut stone lintels and sills, are arrayed in an evenly spaced grid that provides almost the sole source of texture on the building’s flat façade. Where a cornice once capped the building, the façade now ends somewhat anti-climactically with basic coping (1). Between the second and third floors and beneath a row of small rectangular windows are two molded-brick beltcourses with quatrefoil details, offering almost the only sign of ornamentation above the street level. Simple pilasters climb the height of the building, framing its edges and dividing its horizontal mass into sections; they subtly speak to classical revival influences, along with the double hung windows and the (now lost) dentiled cornice. From street level, though, these features are difficult to fully absorb, rising vertically with the mass of the building. A pedestrian’s perspective instead yields a view of the building’s storefront, constructed in 1935 (1), which projects from the flat surface of the building onto the sidewalk. Cast-stone piers capped with Neo-Gothic gablets punctuate the broad retail windows, and leaded-glass transom laced between piers provides a rhythmic border. Orange, blue, and green accents, once vibrant, show signs of fading and deterioration, coupled with peeling finishes and eroding stone. Above each entry, a segmental-arch fascia displays the word “CHAMBERLAIN” in relief, the chipping paint and the label itself speaking to the building’s long history. However, more recent alterations made by Artspace New Haven contrast strikingly with the structure’s humble commercial architecture and historic character, juxtaposing preservation with bold modernity. Two-story supergraphics in powder blue paint (“ART” on the Orange Street façade and “ARTSPACE” above Crown Street) boldly proclaim the power of this building’s presence in the community and speak to the energy of the future of the arts in New Haven. A brightly colored blue and orange storefront frieze displays Artspace’s three ongoing programs—The Lot, City-Wide Open Studios, and Untitled (Space)—in a sort of ticker-tape effect, with seemingly random breaks interrupting the words as their repeated forms wrap around the building. Below this frieze, the two entries are recessed, leading to a modern, spare interior whose clean white walls and open plan are ideally suited for the display of art. A communal office space is visible to the street through large windows, and, often, the gallery’s artworks emit light, or even noise, suffusing the old building with an otherworldly atmosphere pulsing from within.

Works Cited:

1. Maynard, Preston. “Historic Resources Inventory: Chamberlain Building.” Connecticut Historical Commission, 1981.

2. Donald J. Nitz & Associates, Inc. “Real Estate Appraisal, 45-51 & 53-55 Orange Street, Corner Crown Street,” November 1990.

3. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory--Nomination Form.” Ninth Square Historic District: United States Department of the Interior: National Park Service, May 3, 1984.

5. New Haven City Directories, The Price and Lee Co. (1886, 1913, 1924-25, 1933, 1944-45, 1955).

6. Sanborn Map Company of New York, Insurance Maps of New Haven Connecticut, Volume 1, 1886, 3.

7. Sanborn Map Company of New York, Insurance Maps of New Haven Connecticut, Volume 2, 1901, 103.

8. Sanborn Map Company of New York, Insurance Maps of New Haven Connecticut, Volume 1, 1924, 6.

9. Sanborn Map Company of New York, Insurance Maps of New Haven Connecticut, Volume 1, 1973, 5.

10. Yale Furniture Co., Incorporated: CT Open Data. https://www.ctopendata.com/50576-yale-furniture-co-incorporated.

11. Gellman, Lucy. “ACME Closing; 3,000 Artifacts Need Home.” New Haven Independent, September 20, 2016.

12. Miller, Christopher, "Diffuse Aspirations: Mixed-Income Housing in the Context of For-Profit Urban Revitalization" (2011). Student Legal History Papers. Paper 12. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/student_legal_history_papers/12.

13. “Weicker Switch Helps New Haven.” New Haven Register, July 17, 1991.

14. “Ninth Square Vote Hurts City’s Future.” New Haven Register, April 1, 1991.

15. Bass, Paul. “Two Neighborhoods’ Legacies Persevere.” New Haven Independent, August 12, 2015. http://www.newhavenindependent.org/index.php/archives/entry/neighborhoods_revival/.

16. O’Leary, Mary. “New Haven Wants Ninth Square Apartments to Remain Affordable as CHFA Looks for Buyer.” New Haven Register, November 14, 2017.

17. “Artspace Strategic Plan 2017-2020.” Artspace New Haven, October 13, 2016. https://artspacenewhaven.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Artspace-Strategic-Plan-12.21.16.pdf.

18. Chen, Teresa. “Artspace Celebrates 30th Anniversary.” Yale Daily News. April 20, 2016. https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2016/04/20/artspace-celebrates-30th-anniversary/.

19. Croteau, Genevieve. “All New Haven’s A Gallery.” Hartford Courant, October 17, 2002.

20. Kauder, Helen. “Artspace Center for Contemporary Art.” Application for Ruby Bruner Award for Urban Excellence, 2003. https://ubir.buffalo.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10477/35609/Artspace-Center-for-Contemporary-Art_New-Haven-CT.pdf?sequence=3.

Additional Sources:

Burton, Charles Wesley. “Living Conditions Among Negroes in the Ninth Ward, New Haven: A Social Survey.” Civic Federation of New Haven, 1913.

Garbarine, Rachelle. “A New Neighborhood Is Rising in New Haven.” New York Times, August 19, 1994.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Map of New Haven, 1937.

New Commercial Space, Orange Street Between Chapel Street and Crown Street (New Haven, CT). 1998. Photograph. Yale University Visual Resources Collection.

New Haven Tax Assessor's Database: 50 Orange Street. http://gis.vgsi.com/newhavenct/Parcel.aspx?pid=13691.

Orange Street Looking North from Crown Street (New Haven, CT). 1921. Photograph. Yale Visual Resources Collection.

The Residences at Ninth Square. Apartment: 2 Bed/2 Bath. http://www.theresidencesatninthsquare.com/#floorplans.

Vanacore, Ernest J. Looking Toward Knights of Columbus Building Construction from Orange Street Area, Church Street Project Area, New Haven. 1967. Photograph. New Haven Redevelopment Agency. http://connecticuthistoryillustrated.org/islandora/object/280002%3A65.

Brown, Elizabeth Mills. New Haven: A Guide to Architecture and Urban Design. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

Caplan, Colin M. A Guide to Historic New Haven, Connecticut. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2007.

Historic American Buildings Survey. New Haven Architecture. Vol. 159. Washington, 1970.

New Haven Colony Historical Society. New Haven: Reshaping the City, 1900-1980. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

Researcher

Jordan Schmolka, 2018

Date Researched

Entry Created

February 20, 2018 at 2:44 PM EST

Last Updated

May 9, 2018 at 1:06 PM EST by null

Historic Name

Style

OtherGothic RevivalCurrent Use

CommercialResidentialEra

1860-1910Neighborhood

Ninth SquareTours

Year Built

1880-81

Architect

Unknown, alterations by John Weinstein and Michael Haverland

Current Tenant

Artspace New Haven

Roof Types

FlatStructural Conditions

Good

Street Visibilities

Yes

Threats

Neglect / DeteriorationOtherExternal Conditions

Good

Dimensions

102'x117' (both buildings); 109,407 sq ft gross area

Street Visibilities

Yes

Owner

Ninth Square Project Limited Partnership

Ownernishp Type

Client

Unknown

Historic Uses

Commercial

Comments

You are not logged in! Please log in to comment.