Bow Tie Criterion Cinemas (Temple Square)

86 Temple St, New Haven, CT 06510

Bow Tie Criterion Cinemas, at 86 Temple Street, is a well-maintained, lavish-looking movie theater housed in one of the few large office buildings constructed in New Haven during the Great Depression. The United Illuminating building, now called Temple Square, attracts the eye from afar with its brick and marble façade and its ascendant, white clock tower—all surviving elements of the 1939 structure. It looks crisp and bright when compared to its neighbors, including an abutting brick structure on Temple, the New Haven Hotel on George Street, and the Temple Street Garage.

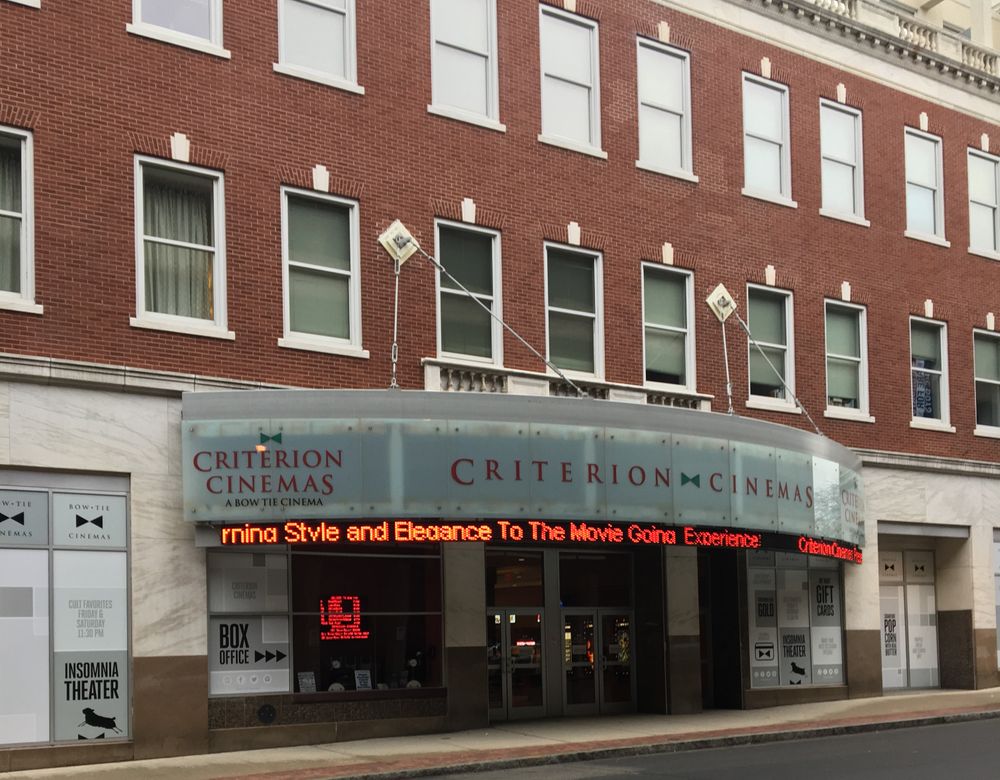

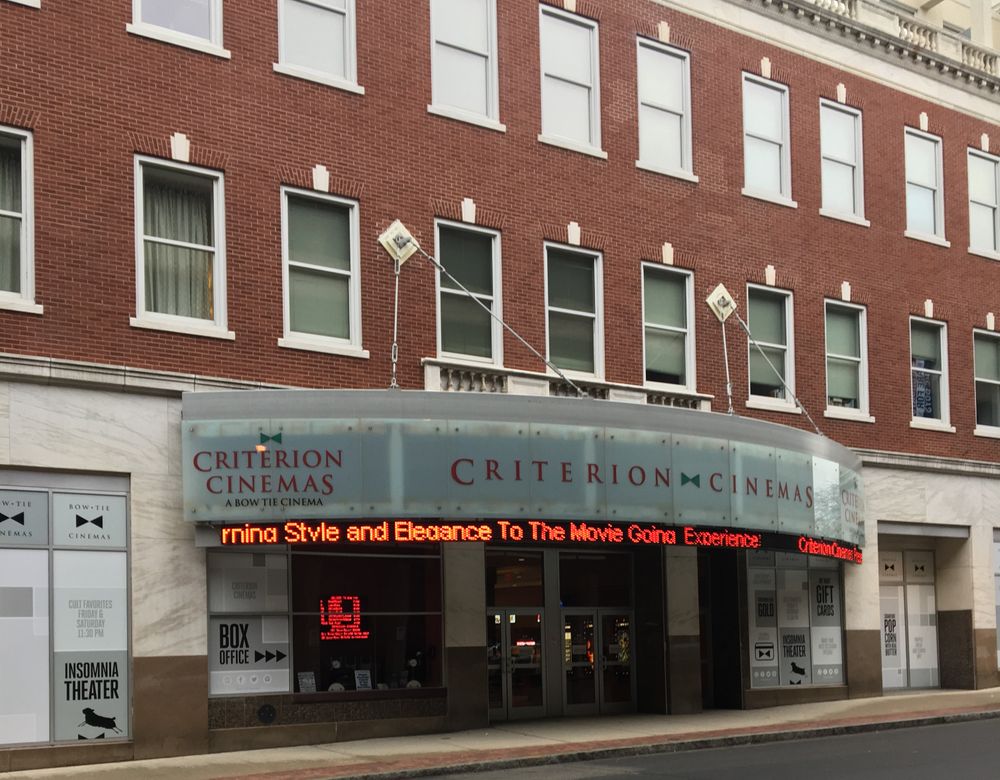

After renovations made in 2003-4 by Bow Tie Partners, the building now sports 44 luxury apartments and the Criterion Theater, which gets its name from Bow Tie’s Manhattan theater. A “cloudlike” metal marquee extends from the Temple Street façade, a semicircular disk that provides shade on the sidewalk and proclaims the theater’s presence in large, red letters (1). Inside, a wide lobby welcomes moviegoers with a red carpet, golden walls, and silver columns; movie posters on either side of the entrance buzz as tiny lightbulbs surrounding them flicker on and off.

When the stately structure was first built, it declared a new technological age for the city—a time revolutionized by refrigerators, dishwashers, and water heaters, all powered by the electricity provided by the United Illuminating Company. Today, housing downtown’s only major movie theater, it undergirds the nightlife first made possible by United Illuminating’s streetlamps, attracting moviegoers to a section of the city once overlooked as “desolate,” “dark,” and “threatening” (2).

(1) Eleanor Charles, “In the Region/Connecticut; Apartments with Movie Theater Set for New Haven,” The New York Times, Apr. 24 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/realestate/in-the-region-connecticut-apartments-with-movie-theater-set-for-new-haven.html.

(2) Scott Healy quoted in Kate Aitken, “Diner Opens on Temple Street,” Yale Daily News, Jan. 12 2006, https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2006/01/12/diner-opens-on-temple-street/; John DeStefano quoted in Melissa Bailey, “Movietime—‘Plus 2’—on Temple,” New Haven Independent, Sep. 15 2006, http://www.newhavenindependent.org/index.php/archives/entry/movietime_--_plus_2_--_on_temple/.

- 1939-1992: United Illuminating Company

- 1992-2004: vacant (owned first by Hartford developer David Chase, then by New Haven's Fusco Corporation. Neither managed to secure a tenant)

One of the earliest depictions of the site is on the 1824 Doolittle Map, which shows New Haven’s Nine Squares after they were split by new streets such as Temple and Crown (17). The corner of Temple and George appears empty on this map, suggesting that the location was either vacant or lacked buildings of significance (as defined by Doolittle and his municipal patrons). The first clear precedent of 86 Temple appears on the 1886 Sanborn Co. map, which displays a small, brick shoe manufacturer identified as Myers and Herz Shoe Co. in the 1888 city directory (18). Surrounding this building are the premises of the New Haven Electric Company (NHEC), from which the utility company provided electric streetlights to the city and private clients. It would become United Illuminating by the turn of the century.

As the NHEC (and later UI) expanded its landholdings along George Street and deeper into the block, the buildings along Temple Street stubbornly held onto their valuable frontage space. The 1911 directory makes no mention of 86 Temple, but the nearby 84 Temple houses the New Haven Progressive Building and Loan Association (19). Close by, where the UI clock tower would soon rise, stood the Eagle Hotel, a wood-frame hotel and saloon that defiantly held onto the street corner. Property owners on Crown Street would at one point band together to “see[k] damages alleged to have been caused by the [electric] plant’s operation”—given the amount of coal required to produce electricity at the time, that damage most likely had to do with the soot falling from the utility’s smokestack, which rose behind 84-86 Temple (20).

By 1924, UI’s success as southern Connecticut’s major electric public utility had allowed it to buy out the property owners on Temple Street. In the 1924 Sanborn map, 82-94 Temple are a series of connected storerooms, housing the materials needed to create the “white-way thoroughfares,” or streets as well-lit at night as during the day, popping up all over downtown (21). The site would exist as such until United Illuminating, having grown out of its administrative headquarters at 124 Temple, chose to demolish the hodgepodge of service and industrial buildings on Temple and George in favor of the 1939 Colonial Revival building, the address of which was 80 Temple. 86 Temple reappeared in 2004 with the opening of Bow Tie Criterion Cinemas.

After laying the cornerstone for United Illuminating’s new administrative building, UI president Albert Kraft “expressed the hope that the employees working in the new and adequate quarters would be able to give the customers the service and attention which they deserve, and thus make it possible for the company to expand in a manner that would be of decided advantage to the stockholders,” according to Kraftsmen, a UI newsletter (14). Yet the structure completed in 1939 and shown to the public in 1940 reflected little of the commercial spirit inherent in Kraft’s statement. Made of brick and marble, with a clock tower to rival the spires on the Green, the Colonial Revival building looked (and looks) more like a city hall or a post office than a company headquarters. This was, most likely, utterly intentional, meant to inspire the same awe and reverence as, say, Boston’s Old South Meeting House. Commercial goals were clothed in civic pride, with “walls of special rough texture brick” hiding the administrative and service headquarters of a regional industrial powerhouse (15).

The United Illuminating Company itself exhibits the same sort of tension between public and private ideals. As a public utility, it has certain obligations toward providing electricity to the residents of its service area, which spans from New Haven to Bridgeport. Yet, in many respects, it effectively operates like a private enterprise, with financial responsibilities toward its stockholders balanced against its semi-public nature. By the 1920s, UI had so successfully met those financial responsibilities that it was one of the city’s largest employers; its influence was often benevolent, helping New Haven attract “new industries” that required large amounts of electricity (3). The murals UI bosses commissioned for the building’s lobby revel in the importance of electricity to modern times. Painted by Jirayr H. Zorthian, the murals depicted Electricity and Light as two gargantuan figures, and traced the development of electric power from ancient times. Seen by UI customers looking to pay their bills or install new electrical equipment, they secured the building’s standing as New Haven entered the postwar era, so much so that it survived the ravages of urban renewal just across the street (see Story Map).

United Illuminating left the building in 1992 to move into a larger, suburban headquarters. When the structure was purchased by Bow Tie Partners in 2003, it began its journey toward becoming a major private anchor of the downtown commercial landscape once again.

Criterion Cinemas sits in a booming residential and retail area that it has helped to foster since opening in 2004. “You couldn’t imagine a more desolate place before Criterion moved in,” the executive director of the Town Green Special Services District told the Yale Daily News (8). And, indeed, this section of downtown was struggling in the years before Bow Tie Partners brought in the theater. The vacant United Illuminating building faced the massive Temple Street Garage, and, beyond that, a gaping hole in the ground left behind when Macy’s department store went out of business. Temple Street was struggling to attract Yale students or the young professionals who were beginning to flock to resurgent cities like New York City and Boston.

But just two years after Criterion Cinemas opened as the “only major movie house in downtown New Haven,” then-Mayor John DeStefano could waltz down Temple Street with a parade of reporters and proclaim, “Temple Street is now turned into a neighborhood” (9) As evidence, he could point to a spate of new restaurants that had opened on the ground floor of the Temple Street Garage to cater to moviegoers; the fact that the apartments above Criterion Cinemas, in Temple Square, were full; and the announcement by Bow Tie Partners that they planned to introduce two new screens to their theater (10).

86 Temple Street’s surroundings today reflect the vibrancy that DeStefano noticed over a decade ago. Across the street, the four-level, concrete garage designed by Paul Rudolph still overshadows the UI building, but its ground floor hosts eateries like Roly Poly Sandwiches and Pho Ketkeo, a Laotian restaurant. A few buildings down is Olives and Oil, a wine bar occupying another former headquarters of United Illuminating. Barcelona Wine Bar also sits nearby. Criterion Cinemas anchors this restaurant and bar landscape, inviting students and professionals to couple movie-watching with bar-hopping. “The Criterion is to this side of town what the Shubert [Theater] and the [Yale Repertory Theater] are to Chapel Street,” DeStefano said in 2006 (11).

The UI building is one of the few Colonial Revival structures in this area, which is otherwise dominated by modern (and postmodern) facades. Importantly, the neighborhood does not yet look fully developed. It’s still in the process of revitalization—or gentrification, according to people who note the 250+ new, luxury apartments (12). Slices of surface parking cut into the block on which Criterion Cinemas sits, suggesting the potential for further building. It’s likely that future construction will lead to more structures like Temple Square, specializing in the same sort of “CORPORATE HOUSING…[with] short term and flexible leases” rather than middle- to low-income housing or retailing (13).

Located on the ground floor of the Colonial Revival United Illuminating Building, now known as Temple Square, Bow Tie Criterion Cinemas proclaims its presence on the sidewalk with a grand, semicircular metal marquee. This metal apparatus, hanging from the brick façade by suspension cables, appears to float above entering moviegoers, a “cloudlike” half-moon that displays movie titles and shelters pedestrians from the rain (1). Illuminated by hidden interior lights, it speaks to the building’s long connection with electricity and industry.

Criterion Cinemas and its marquee were introduced to this 1939 structure in 2003-4, when Bow Tie Partners, a New York real estate developer and theater operator, purchased the vacant building and “gutt[ed] and remediat[ed]” much of it (2). The original façade, designed by R. W. Foote, remains—parallel planes of ground-floor white Vermont marble and upper-floor red brick extending more than a hundred feet down Temple and George Streets. Anchoring the building’s L-shape is its raised, four-faced clock tower, also made of Vermont marble and topped with a “polygonal lantern with small arched windows on each side” (3). It calls to the white spires on the Green for which Temple Street is named. While the tower’s windows are Palladian, the façade’s glass portals are more typical of neocolonial architecture, with two panes bisected horizontally by a thin, white divider. Facing the building from Temple Street, its façade appears U-shaped, with the clock tower rising a floor above the rest of the structure on one end, and a less ornate tower doing the same on the other. Paradoxically, the central Criterion marquee, a floating breath of metal amongst the brick and marble, seems to hold the structure to the earth.

Although the façade has remained mostly untouched, the interior was transformed in 2004. When the building was first constructed, it served as a multipurpose headquarters for one of New Haven’s largest utility companies—as such, its spaces were large and varied. Into this 112,000 square-foot structure, Foote crammed spaces for United Illuminating’s “administrative, sales, service, storage, repair and garage divisions”; one area, the “Demonstrating Auditorium,” showcased the electrical marvels of the interwar period: “ranges, water heaters, refrigerators, dishwashers, disposal sinks and small appliances” (4).

Bow Tie Partners, headed by Charles and Benjamin Moss, turned these commercial and administrative areas into 44 luxury apartments, Criterion Cinemas, and as-yet-unoccupied restaurant spaces. The Art Moderne movie theater lobby that resulted from these renovations sparkles with red carpets, golden walls, and metallic columns. Movie posters on its walls crackle as the lights surrounding them audibly buzz on and off. Furman & Furman, the firm that designed the theater, aimed to create a “gathering place” which recalled the grandeur of the original building (5); this was achieved by including not only a café area, but also five-foot panels showing “switches, dials, gauges, and other electrical equipment” from United Illuminating (6). Though those panels no longer grace the lobby, a large mural, hanging over the café tables, speaks to the structure’s history with pictures of Bow Tie’s founders and the old UI building. Notably, the 1939 building also displayed murals in its public-facing spaces, including two by Yale graduate Jirayr H. Zorthian. The murals used allegorical figures to represent Electricity and Light—under Electricity’s right arm were “four great scientists who were pioneers in the discovery of this great power. They are: in the background, Thomas Edison; on the left, Michael Faraday; in the center, Count Volta; and on the right, Benjamin Franklin” (7). The current mural in Criterion’s lobby connects the relatively new space to this long history.

(1) Eleanor Charles.

(2) HBH Construction, “Criterion Theater & Apartments,” http://www.hbhconstructionllc.com/865004006353/.

(3) Preston Maynard, “Connecticut Historical Commission Historic Resources Inventory: United Illuminating Co.” (Hartford, CT, 1981), 2.

(4) John D. Fassett, “UI: History of an Electric Company” (1990), 256.

(5) Richard Furman quoted in Charles.

(6) Eleanor Charles.

(7) John D. Fassett, 259.

(8) Scott Healy, quoted in Aitken.

(9) Eleanor Charles; John DeStefano quoted in Melissa Bailey, “Temple Comeback,” New Haven Independent, Apr. 3 2006, http://www.newhavenindependent.org/archives/2006/04/temple_street_u.php.

(10) Melissa Bailey.

(11) Melissa Bailey.

(12) Eleanor Charles, “Commercial Property/Connecticut; Downtown New Haven’s Multifaceted Rehabilitation,” The New York Times, Sept. 29 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/09/29/realestate/commercial-property-connecticut-downtown-new-haven-s-multifaceted-rehabilitation.html.

(13) “Temple Square,” ApartmentGuide.com, https://www.apartmentguide.com/apartments/Connecticut/New-Haven/Temple-Square/45644/#floorplans_and_pricing.

(14) John D. Fassett, 269.

(15) John D. Fassett, 256.

(16) “National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Chapel Street Historic District” (Hartford, CT), 9.

(17) Amos Doolittle, “Plan of New Haven,” 1824. Accessed through http://gatheringabuilding.yale.edu/#/routes/historical-geography.

(18) Sanborn Map Company, New Haven Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1886; “New Haven City Directory 1888” (New Haven, CT, 1888).

(19) “New Haven City Directory 1911” (New Haven, CT, 1911).

(20) John D. Fassett, 78.

(21) Sanborn Map Company, New Haven Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1924; Maynard.

Researcher

Robert Scaramuccia

Last Updated

February 28, 2018 at 11:32 PM EST

Style

Colonial RevivalCurrent Use

CommercialEra

1910-19501980-TodayNeighborhood

OtherOtherYear Built

1938-39

Architect

Roy W. Foote (exterior), Furman & Furman (interior)

Current Tenant

Bow Tie Criterion Cinemas

Roof Types

FlatStructural Conditions

Very Good

Street Visibilities

Yes

Threats

None knownExternal Conditions

Very Good

Dimensions

177.5' x 198' (UI Building, before renovation)

Street Visibilities

Yes

Owner

Bow Tie Partners

Client

United Illuminating (original), Bow Tie Partners (rehabilitation)

Historic Uses

Commercial

Comments

You are not logged in! Please log in to comment.